COVID-19 digital contact tracing worked - heed the lessons

Data show that these privacy-preserving tools saved thousands of lives during the pandemic. National and international authorities must invest in the technology now.

This week, I’ve had the opportunity to share my thoughts on the history and potential future of digital contact tracing in Nature (here’s the piece, open access).

Given severe space restrictions in the journal, I’d like to add a few important aspects that didn’t make the final cut.

First, I’m deeply grateful to Christophe Fraser and his team at Oxford University, particularly Michelle Kendall. Their research papers were the catalyst that spurred me to write this piece. As I said previously, without their work, we’d still be in the dark about the effectiveness of digital contact tracing.

With that said, what follows are my personal opinions based on my experience in the development and deployment of the tech. I believe there are some important lessons for the future of governmental technology development there.

Many European governments did not want privacy preservation

When we presented the idea of decentralized, privacy-preserving contact tracing, many European governments had absolutely no interest in it. Indeed, they fought quite hard to get Apple and Google to reverse their stance, and to allow centralized contact tracing within the Exposure Notification framework (luckily, they did not succeed).

For quite some time, I had thought that perhaps it had all been a big misunderstanding, and the governments really didn’t care too much either way - perhaps they just wanted to have digitally what they were used to in the analog world.

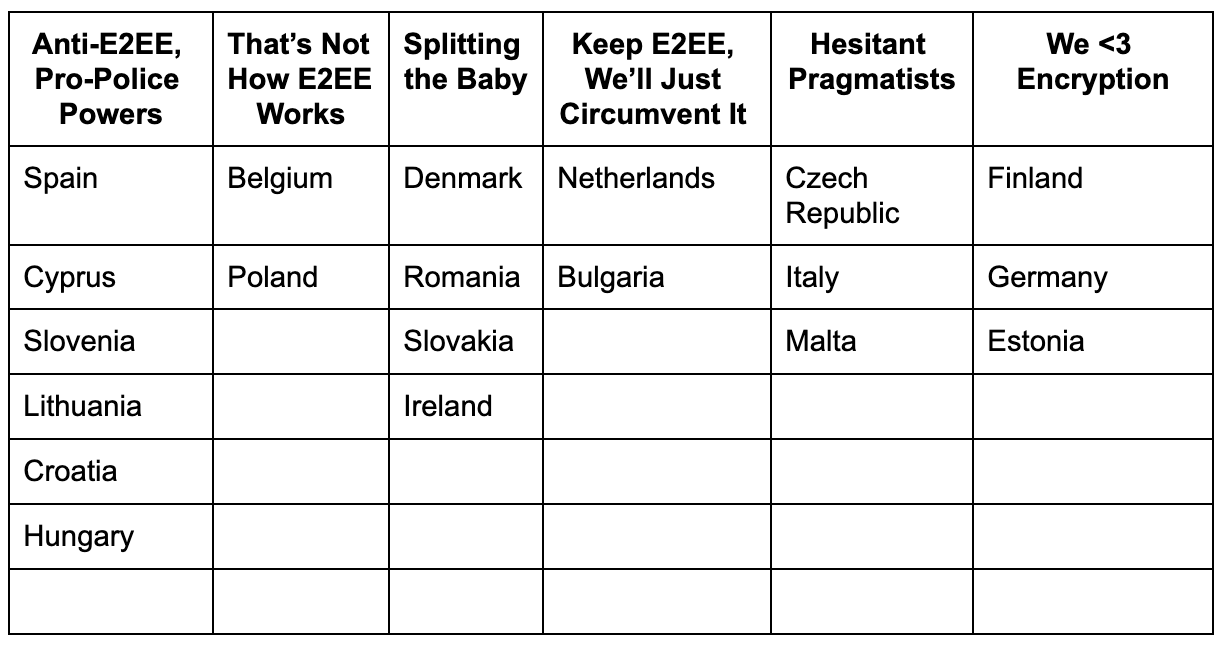

But the EU’s proposal to ban end-to-end encryption put a nail in the coffin of that dream. The UK government wants to ban end-to-end encryption with the Online Safety Bill. Spain has lobbied in the EU to ban end-to-end encryption. Many other governments, including Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Lithuania, and Cyprus, have demonstrated strong support for the ban. Here’s a table from a fantastic write-up by the Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law School about each EU member state’s stance on the proposal:

I’m particularly shocked by the stance of governments, whose people have suffered from extremely intrusive Soviet-style surveillance not too long ago.

The reason given is always the same: they want to scan private messages for illegal content. “In order to protect you from bad things happening, you must forgo your privacy.”

Sounds familiar?

This was the exact same argument they used to advocate for centralized contact tracing. As the Economist put it at the time, “if covid-19 becomes a pandemic, [people] may well become more inclined to forgive a more nosy use of personal data if doing so helps defeat the virus.”

Today, we know that privacy preservation and fighting a pandemic are not mutually exclusive goals.

(A local side note: The Swiss government did embrace and support decentralized, privacy-preserving contact tracing from the very beginning. I’ve been on the record as being quite critical at times about my own government’s decisions regarding the pandemic. But their commitment to privacy preservation was rock solid in early 2020. That’s something I'll never forget.)

As is often the case, the world is more complicated than it seems. The narrative of “big tech bad, public health authorities good” was clearly violated during the development of digital contact tracing. As governments become more digitized, we need to be extremely mindful of the potential for overreach on both sides. We’re often given the choice between digital convenience and privacy. Digital contact tracing demonstrated that this is a false choice.

People think digital contact tracing failed

Ask anyone whether digital contact tracing worked, and the answer will most likely be “I don’t think so”. As I pointed out in the comment, to the extent that it didn’t work, it was mostly related to two aspects: 1) the poor integration of the technology, and 2) low usage.

Imagine you had a vaccine that needed to be stored at cold temperatures. During a pandemic, the vaccine is deployed, but mostly without refrigeration, and only about 20% of the population end up taking it. Would you conclude that the vaccine failed?

Of course not. You would try to find a country where the deployment was done properly, at the right temperatures, and where you would have enough data to assess the effectiveness of the vaccine.

This is exactly what we have here - the country is the UK, or England and Wales, to be more precise. The data show that during the first year, the app prevented at least 9,600 cases, 44,000 hospitalizations, and a million cases. All of this with a usage of only 25%.

You don’t need very advanced math to realize the potential here. Imagine if most countries had deployed digital contact tracing like England and Wales. Further imagine that 3 in 4 people had used it, instead of just 1 in 4. It’s possible that the technology could have saved hundreds of thousands or even millions of lives. It’s even possible that the technology could prevent a future pandemic altogether.

While it would be silly to argue that one measure will be enough, I will never tire of advocating for digital contact tracing, for three reasons. First, it is very non-invasive. Just download the app, use it, and go into quarantine if you are asked to. If we can’t do that, I’m not sure we’ll ever be able to stop a pandemic. Second, it is very cheap. Developing and deploying the technology isn't free, of course, but compared to the enormous costs of the alternatives, it’s a steal. Third, all of this comes at essentially no risk to privacy.

Seriously, what else could we ask for?

Nobody is investing in the technology

To some extent, the lack of investment in this technology is not overly surprising, given that most people wrongly believe that the technology failed.

However, policymakers should base their actions on more than just belief, and take a hard look at the data. In this case, the data is telling an increasingly clear story. This was, of course, the main message in the Nature comment:

“Health authorities must prioritize privacy-preserving digital contact tracing, and governments must commit to long-term investments in this area. But it is just as important that public-health systems become more digitally savvy.”

One of the most puzzling questions is whose role it is to further the development of digital contact tracing technology. As I point out in the comment, the WHO is not the right actor because it lacks the necessary technological competence. I wasn’t able to find a single document by the WHO that suggested further development of this technology. The ITU, the UN’s agency for information and communication technologies, suffers from debilitating political paralysis. It seems to me that a new “coalition of the willing” - perhaps loosely composed of researchers and other stakeholders - would be necessary to take the lead.

The key issue, in my view, is long-term funding, which should in principle be provided by governments but may more realistically come from philanthropic funders.

Importantly, we should use the time available now to ensure that experts from all relevant fields are involved. We’ve already demonstrated that epidemiologists and privacy experts can work together to develop powerful digital health technology. However, the key issue with digital contact tracing was that a) people did not trust the technology, and b) people did not believe it would work. It will take experts from psychology, UI design, and many other fields to ensure the next app - on whichever platform it runs - will not be underutilized.

Last but not least, public health authorities need to seriously upgrade their digital infrastructure. I'm not just talking about abandoning outdated technologies like fax. Apart from pharmaceutical solutions, which take time to develop, digital technologies provide us with a means to outpace whatever challenges nature might throw at us in the future. We simply can't afford to lose this race by consistently being two or three decades behind the technology curve. Even the best contact tracing app will falter if it can’t be properly integrated into the existing public health infrastructure on the ground.

CODA: Where to find me

I’ll make it a habit in these posts to remind people where to find me:

Writing: I write another Substack on practical tips for interacting with large language models, called Engineering Prompts.

Great post, as usual! About WHO not support any directions on the use digital contact tracing, actually in a very recent piece they published (Defining Collaborative Surveillance - https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240074064), they mentioned four times "contact tracing" term in the whole document, where only one occurrence the context matches you concern: "applying digital tools for contact tracing and case management". Very very far from the ideal, but it might be a beginning of a slow-pace change.